Credit: Thinkstock

Scientists are scared. Not of the more mundane scary science stuff, like global warming or measles outbreaks, but of a more exciting, exotic apocalypse. At an American Association for the Advancement of Science conference in San Jose, California, last week, some scientists warned that sending messages into space might lead to extraterrestrial invasion—and the end of life as we know it.

Science-fiction writer and scientist David Brin was particularly upset at the suggestion that the SETI institute might start broadcasting to nearby stars. "Historians will tell you that first contact between industrial civilizations and indigenous people does not go well," Brin warned. "The arrogance of shouting into the cosmos without any proper risk assessment defies belief. It is a course that would put our grandchildren at risk."

If the comparison between aliens and European conquerors sounds familiar, that's no accident. Science-fiction has compulsively replayed colonial invasion narratives since its inception. In The War of the Worlds, H.G. Wells directly compares his invading Martians to European conquests in Tasmania; what we did to them, Wells says, the Martians will now do to us. The same story, only slightly rejiggered, shows up in The Avengers, with its extra-dimensional invading conquerors, and for that matter in Pacific Rim, with its submarine invading monsters. Somewhere out there, the story goes, some other Columbus is going to lead some other people to our borders, and the result will be an all-too-familiar genocide.

The repetition of the same fear seems somewhat compulsive—and oddly unimaginative, especially considering that we're talking about contact with aliens. Aren't there other possibilities for contact beyond violent extermination and war? Does contact really have to mean genocide?

Enter Octavia Butler

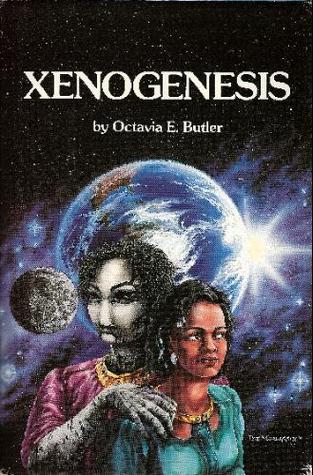

There have been other sci-fi approaches, of course. 2001 imagined a kind of beneficial colonialism, with an advanced race from beyond the stars arriving on earth to teach the savage ape men to use tools. But one of the most interesting narratives of alien contact is less well-known, and more ambivalent: Octavia Butler's Xenogenesis trilogy, also known as Lilith's Brood, from the 1980s.

Butler's story has elements of the 2001 savior narrative; her aliens, the Oankali, arrive on earth following a devastating nuclear war between Russia and the U.S.; the Oankali rescue the few survivors. Xenogensis also has aspects of the H.G. Wells conquest story though—with a twist. The Oankali don't want to kill humans; they want to mate with them. They're a race of genetic manipulators; they roam the cosmos trading with (that is, having sex and babies with) other living beings. They're especially attracted to humans—not because of human's indomitable spirit, but because humans get cancer, a genetic quirk that is hugely attractive, and useful, to the Oankali.

For Butler, then, alien invasion doesn't mean human extinction, nor does it mean, exactly, human transcendence. Instead it means lots of tentacle sex, and bizarre transformation; human/Oankali kids are a mixed, heterogenous group of human bits and pieces and precocious octopoids.

That's icky and uncomfortable—and it's supposed to be. Humans, Butler says, are terrified of difference. When Lilith, rescued from earth's destruction, is woken on the Oankali ship, and confronted with one of the Oankali, she reacts with a phobic fear. "She did not want to be any closer to him. She had not known what held her back before. Now she was certain it was his alienness, his difference, his literal unearthliness. She found herself still unable to take even one more step toward him." Later, one of the Oankali named Nikanj explains that "Different is threatening to most species . . . Different is dangerous. It might kill you."

That's the calculus David Brin is using when he worries about beaming a message into the stars and attracting some alien Columbus. And, as Nikanj says, that fear is understandable. But if different is dangerous, so is fear of difference. Lilith is unusually adaptable; she's able, eventually, to accept the Oankali, and even to mate with them. Other humans have more trouble—and those who really cannot accept difference end up dead. The old earth is gone; the only way forward is the Oankali way. Those who can't deal with difference in their culture, and even in their families, are left with no options but murder and death. In Butler's world, that's how humans ended up destroying the earth in the first place.

The discussion of difference in Xenogenesis is further complicated by the fact that the book's author, and its main characters, are black. Because she is able to accept, and work with, the Oankali, other humans see Lilith as a traitor and an alien herself—which in the racist, real, non-science-fiction world, is of course exactly how black people are often viewed. Lilith, a black woman, is in part a stand-in for all the non-white people colonized by aliens throughout history. But she's also a reminder that seeing people as different and alien has generally, historically, meant seeing black people as alien. Lilith's children are black, literally alien, and, in numerous ways, superior. A world conquered by difference may be frightening to David Brin, but for Butler and her black characters, who are identified with, and can identify with, difference, the overthrow of life as we know it has some upsides.

Octavia Butler's Oankali and H.G. Wells' Martians aren't real; they're not really going to breed with us or exterminate us. But while fictional aliens aren't a threat, our fictions about aliens might be. If we can only think of difference as violence, then violence becomes, Butler suggests, a self-fulfilling prophecy. The future isn't in the stars, but what we see in the stars may be our future—whether genocide or tentacle sex, as the case may be.